On Friday, regulators shuttered Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the U.S.’s 16th largest bank with some $200 billion in assets at its peak, and, more importantly, the bank catering to America’s (the world’s) technology and venture capital hub.

The second largest bank failure in American history was also the fastest. SVB was officially euthanized just two days after its troubles made front page news. The story, and more importantly, what’s next—regulatory response, rescue scenarios, contagion possibilities, and market fallout—are all still developing.

Here are five initial thoughts on the mess.

1. SVB was uniquely vulnerable to a classic bank run.

Its focus on the Silicon Valley ecosystem, arguably the most volatile and herd-like in its oscillating between fear and fear-of-missing-out, was but one driver of its concentration of risks. Bank deposits nearly tripled to $200 billion from the end of 2019 to the first quarter of 2022, a growth rate that was five-times the rate of banks nationally. “Uninsured deposits,” meaning customer deposits more than the $250,000 per customer insured by FDIC, was north of 94% of total deposits (I’m not aware of another large bank that comes close).

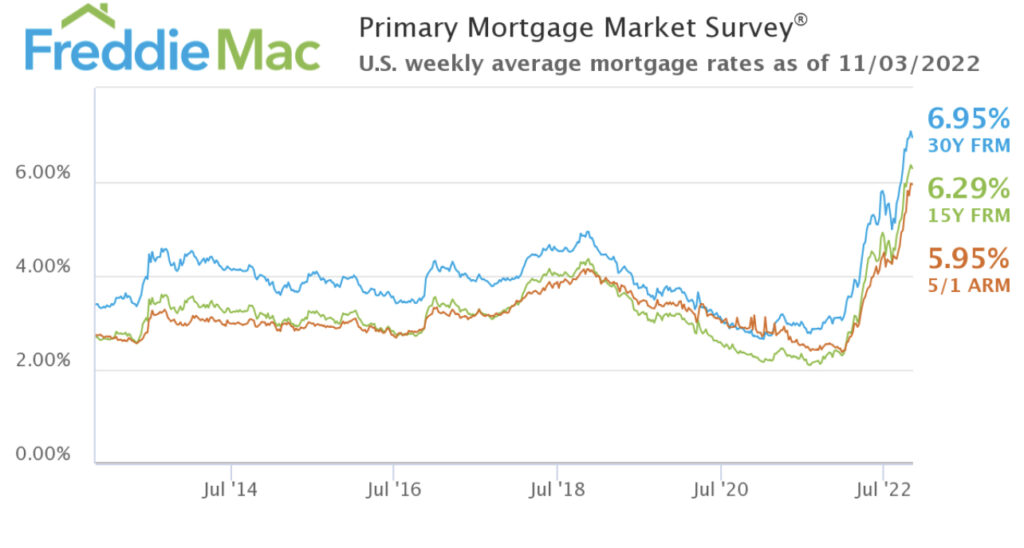

What SVB’s management did with the windfall deposits was a colossal failure (there’s just no diplomatic way to put it). An inordinate amount of the money was invested in high quality, but longer term, government and agency notes—much of it at historically low yields prevailing in 2020 and 2021. Yields that were likely closer to 1.5% than 2.0%, and yields that were only less than half a percent more than shorter term securities.

Rather than typical bank collapses caused mostly by bad loans and securities, SVB’s failure seems to have been a massive duration mismatch. It either (1) failed to realize the nature of its massive deposit inflows was possibly the “easy come, easy go” type; or (2) deliberately took risks reaching for yield at the worst possible time; or (3) both. The crypto and tech downturn meant short term deposits were even shorter, forcing SVB to sell investments at a good loss and slash its capital cushion. A vicious cycle of unprecedented speed ensued.

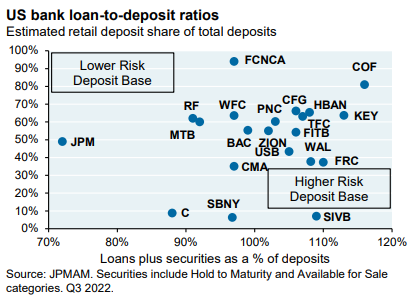

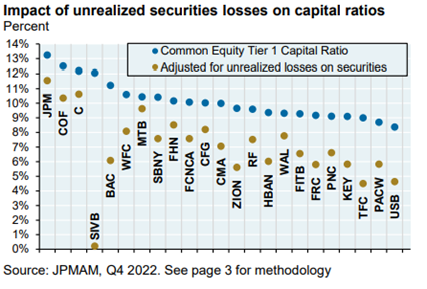

Two charts from a J.P. Morgan report Friday show how far SVB was in customer concentration (less “retail” means fewer, larger customers) and exposure to investment losses. (1)

2. The Real News: many banks have a problem in unrealized losses.

This is a big deal, so bear with me for a minute. Nearly 40 years of declining interest rates helped unleash high economic growth and massive fortunes. That means millions of people in business, finance, real estate—you name it—have lived and worked knowing capital to get only cheaper.

That all changed in 2022. It turns out interest rates can go up. Money can get more expensive, even sharply so. Refinancing may not be an option. And bonds, regardless of quality, can drop in value suddenly and for a long time.

That last part was especially missed when, in the aftermath of banking crises, including The Great Financial Crisis, regulators focused on banks’ having more equity (assets minus liabilities) and credit quality. What regulators and bankers largely ignored over time are the average maturity of those assets and more nuanced but important risk considerations. For example, having deposits almost entirely funded by a few depositors (who talk to each other) is an atypical and riskier funding base, all else equal. This wasn’t reflected in how SVB invested assets.

The bank business model is basically this: borrow short term, lend long term. They borrow from depositors—us—accepting we can take deposits out of the bank at any time. Banks lend longer term, through mortgages and loans, and by buying loans, through securities.

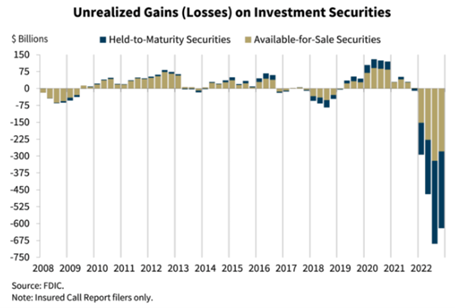

Securities assets on a bank balance sheet are either classified as Available for Sale (AFS) or Held to Maturity (HTM). The former is assumed to be a source of cash when depositors need their money; the assets are priced on a “mark-to-market” basis, meaning the gains and losses in the portfolio are booked quarter to quarter. HTM assets are not marked-to-market and represent a commitment by management not to sell before maturity. HTM assets are immune from market fluctuations, accounting-wise. Price movements have no effect on reported earnings or the balance sheet.

This changes, however, if the bank sells any of its HTM assets. Unless management can convince auditors otherwise, a single sale from the HTM portfolio constitutes the entire portfolio be marked-to-market.

For decades, unrealized losses did not matter because interest rates only went down and prices moved up. That’s all changed, and now some banks are finding they are not that different from SVB: if a small fraction of the deposits is withdrawn, a bank would have to realize losses on their entire HTM holdings. For some banks, those realized losses would wipe out most or all of their equity/net worth! Today, many conservative banks find themselves in crisis.

Total unrealized losses for the banking sector stands at over $620 billion, according to FDIC. (2)

3. Bailouts are back to stop contagion.

After a myriad of bailouts and new regulations almost 15 years ago, Treasury and the Federal Reserve vowed an end to bailouts. Nothing was going to be Too Big to Fail going forward. That resolve was broken by its first test in SVB.

Over the weekend, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced no bailout was in the works. If you think about it, SVB is the worst bank to bailout, politically speaking. SVB is as far as it gets from a Main Street bank. Ultimately, principles were cast aside for fear of imminent bank runs across the country. A full bailout was announced for SVB and New York’s Signature Bank (which was shut down over the weekend). All depositors will be made whole.

Contagion is still possible, at least that’s what today’s market action is telling us. Besides, many banks’ balance sheets now look vulnerable—especially smaller banks.

4. Is your money in danger?

Those with more than $250,000 in a bank should consider taking measures. Bank runs are a form of Prisoner’s Dilemma: there’s no downside to being the first to take uninsured deposits out. Treasury bills are a far safer—and higher yielding—place to park large amounts of cash. I’m wondering if a typical bank’s existence today is only possible because large numbers of people choose to underearn by parking money there instead of earning the higher yields (with lower risk) offered by Treasury bills. The basic borrow short/lend long business model of traditional banks has been increasingly threatened over time. Competition, regulation, and the internet have eroded the competitive position of banks. The run on SVB was the first of the smart phone age and one where the run was mostly people issuing wires from their phone or other device.

Bottom line: There is still no reason to park large amounts of cash at a bank.

5. The Fed’s job gets difficult from here.

The Fed has wasted no opportunity in expressing a hawkish prioritization of slashing inflation quickly. Just last week, markets had priced in a 0.5% rise in the Fed Funds rate at the Fed’s next meeting on March 22. Today, the question is whether they will raise rates at all.

The room for policy error has risen a lot. To that end, we’ve further decreased our allocation in stocks while emptying our exposure to government agency notes. Our fixed income investments are still short term overall and in U.S. Treasurys. We work to keep assets off brokers’ (or banks’) balance sheets (no margin accounts, Treasury bills in favor of bank sweep accounts).

Many developments to come, surely. We will keep you updated.

(1) Michael Cembalest, J.P. Morgan, “Eye on the Market” March 10, 2023.

(2) Chrisitan Hetzner, “SVB Collapse Highlights $620 Billion Hole Lurking in Banks’ Balance Sheets.” Fortune Magazine online, March 10, 2023.

The content provided in this document is for informational purposes and does not constitute a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to purchase or sell securities. Nothing should be considered personal financial, investment, legal, tax, or any other advice. Content is information general in nature and is not an attempt to address particular financial circumstance of any client or prospect. Clients receive advice directly and are encouraged to contact their Adviser for counsel and to answer any questions. Any information or commentary represents the views of the Adviser at the time of each report and is subject to change without notice. There is no assurance that any securities discussed herein will remain in an account at the time you receive this report or that securities sold have not been repurchased. Any securities discussed may or may not be included in all client accounts due to individual needs or circumstances, account size, or other factors.

It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed was or will prove to be profitable, or that the investment recommendations or decisions we make in the future will be profitable or will equal the investment performance of the securities discussed herein.