(Why I don’t need to write about banks again)

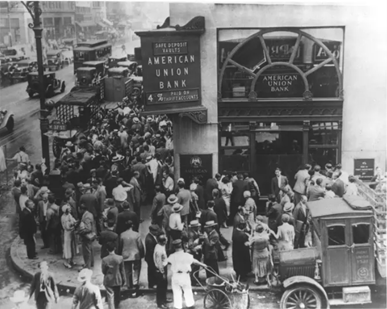

Last week, the former Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) chief testified before the Senate Banking Committee. The scene was predictable. Outraged Senators lambasted. A CEO apologized but accepted no blame for his bank’s demise. Every participant sounded incompetent.

The FAA investigates and studies each airplane crash, and more importantly, is effective in making flying safer afterward. Crashes, while tragic, save many lives later.

If only government were this good with banking. A bank crash seldom leads to better outcomes later. Some would disagree, but I believe it is true that banking failures and financial crises do little in making the system less fragile. Crashes here are often in vain or worse.

What emerges from a money-related crash is something bigger, more centralized and homogenized, more at stake for taxpayers—and paradoxically more vulnerable. It’s as if the industry and government look at the last crisis as something revealing the one risk we overlooked, the final piece to a failsafe system going forward. The problem, of course, is basing everything on the known past makes us all fragile to the unknown future. The next war will be different than the last one—and perhaps more damaging with each bailout, can-kicking, and doubling down on policymakers’ control. The stakes continue to mount. The price of failure continues to escalate.

I wish I could find some new insight from recent events. Instead, banks’ current troubles—like the ones before it—only seem to harden my jaundiced view of banks and banking. I’ve long thought if one understands that their deposits are actually a loan to the bank, they would save differently. I think if people knew about Treasury bills, few would ever carry large sums at a bank. And almost no one would consider buying a CD (which almost never yield more than a Treasury bill, especially after tax).

I have no interest in politics or telling how the world should be. An investor’s job is to observe what is and endeavor to make rational decisions.

The only thing that matters when it comes to banks is this: banks are risky and always have been—act accordingly. This sounds glib but sometimes the truth is. I tried finding something new and useful with the latest bank chapter. I have nothing.

This is not to suggest avoiding banks but instead to approach banks as you would any other business where you are the customer. Expect more value than you pay. Insist the bank is deserving of your deposits (i.e. Well run, conservative, and paying a reasonable price for holding your money).

Banking is a challenging business even with docile customers expecting and accepting a customer experience only slightly better than the DMV.

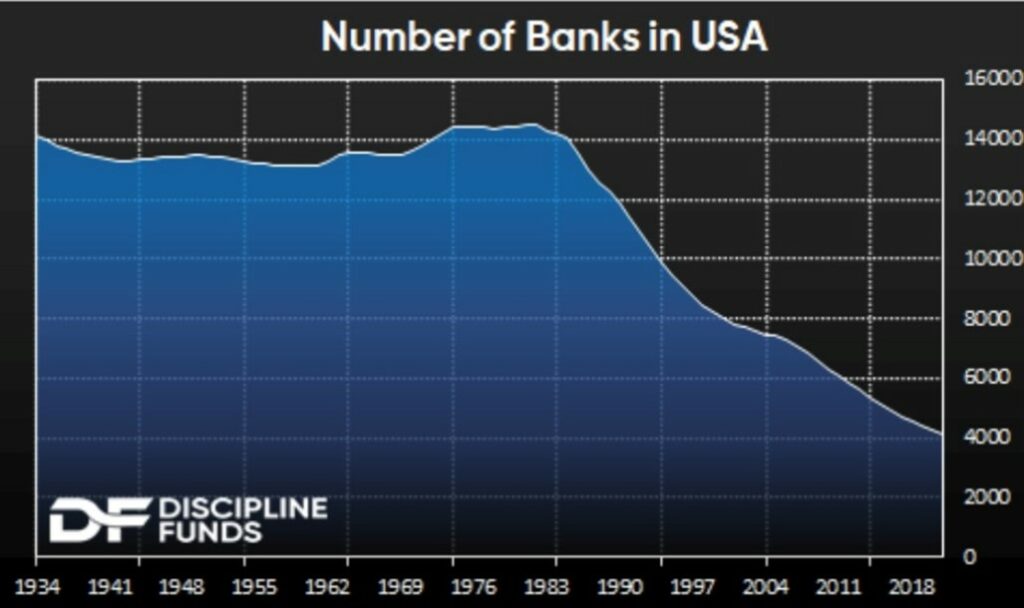

Troubles have been forming for a long time, especially smaller ones who previously enjoyed home-field advantages and being a big fish in a small pond. The number of banks continues to dwindle. I see no reason for the trend to reverse with increasing scale advantages of large banks, along with customers thinking about yield and credit for the first time in generations.

Almost 14,500 commercial banks existed in the U.S. 40 years ago when their numbers started an inexorable decline. The count has declined 70% since, even as the number of branches across the country has almost doubled, and the money parked in them has grown 10-fold. Fewer banks haven’t decreased accessibility even if differentiation among banks has fallen. Banking has become commoditized by design. The unintended consequence is redundancies. Markets deal with redundancies rather efficiently.

Regardless of the banking landscape, now is as good a time as any to reexamine the odd nature of the bank and how we use them.

Get risk-free return instead of return-free risk

Unlike other businesses providing a product or service customers want, the banking business model requires an indirect and loosely symbiotic relationship with most of their customers. Banks make most of their profits by making longer term loans. Some of these loans are in the form of securities; we call most of these securities “bonds.” (Think of bonds as tradable loans.)

The loans and securitized loans (bonds) are assets on a bank balance sheet. The source of funds to make these loans is from customers (depositors) who give their money to banks for safekeeping. Some depositors are motivated by yields, but most stop paying attention and inertia sets in. But no one deposits money into a bank because the bank is going to loan out their money and impose credit risk on them.

These deposits are short-term obligations or liabilities, meaning depositors can generally pull their funds at any time even though their money collectively is almost all deployed in longer term assets. (Once a bank makes a 30-year mortgage commitment, the borrower has no obligation to repay early.)

The “borrow short, lend long” business model is a problem and always has been. Credit risk is a constant, if varied challenge, as are interest rates. Banks want low short-term interest rates and higher long-term interest rates. Banks are in control of neither, nor are they in control of when (or how much) their main funding source—deposits—leaves, nor can they determine when (or how many) of their borrowers will refinance to lower interest rates.

These challenges were also faced by SVB. However, these risks should have been more acute to SVB’s management than to any other large bank in America. The bank had the industry’s fastest growing deposit base; the largest percentage of large depositors (some 97% of its deposits were above $250,000); and the highest concentration in the Silicon Valley venture capital and tech start-up world. Deposits were concentrated-squared.

It didn’t occur to management their deposits could be easy-come, easy-go, or that depositors were highly correlated to one another. (As in, a slump in tech valuations would mean not just one mega-depositor would need to pull its funds.)

Management also never considered longer term interest rates could rise. The SVB CEO’s excuse to the Senate was he trusted the Fed’s outlook that inflation was “transitory.” In the end, caught with too many long-term bond investments that were underwater while large depositors pulled funds, SVB failed, even if it officially passed the more stringent capital requirements imposed by the Fed and Congress after 2008.

To be sure, the way SVB failed or Signature Bank or First Republic Bank or Washington Mutual, or the many banks that failed before it, are not the only ways a bank can fail. Not all risks and contingencies have been accounted for.

No matter. By electing for so called “risk-free return” in shorter term Treasury bills instead of virtual “return-free risk” with a bank, we don’t need to be victims of a failed bank or even be burdened with keeping an eye on our bank’s solvency.

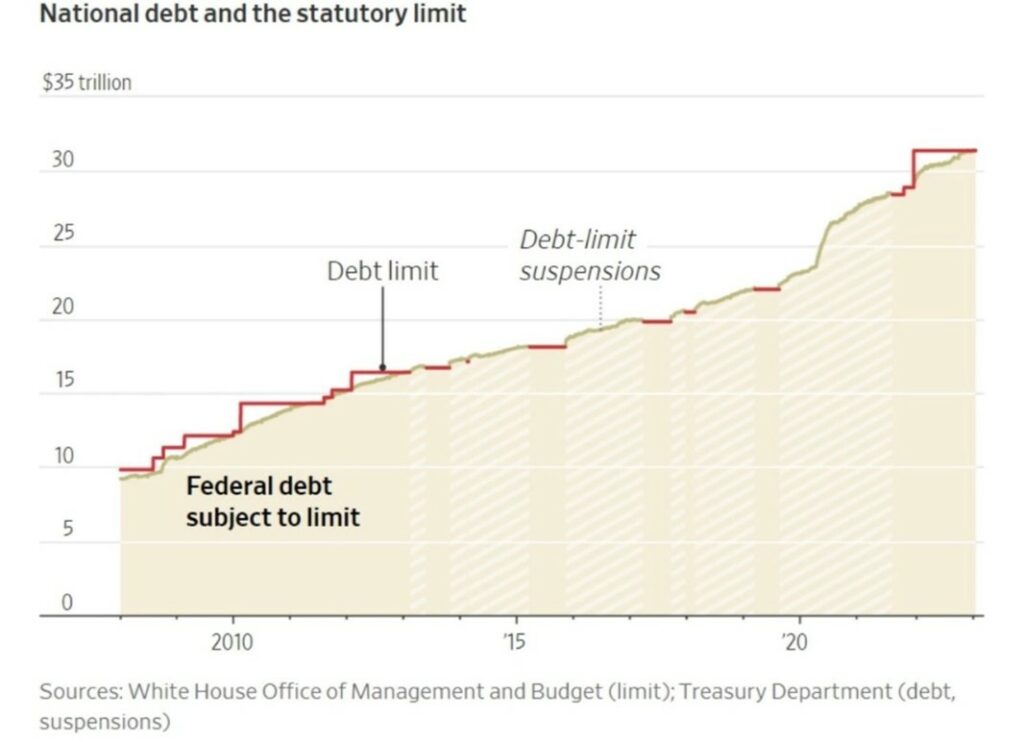

I hope this is the lesson people learn from this crisis, that they can earn more yield in Treasury bills (with great liquidity and no state income tax) with a better credit (the U.S. government) than bank products. More yield and safety for big money and small. The looming debt-ceiling crisis is nothing to fear. The federal government won’t default. It can’t default (it’s in the Constitution). Treasury interest and principal must be paid before anything else, period. The dozen or so debt ceiling breaches since 2008, including a couple of prolonged government shutdowns, did nothing to the sanctity of Treasurys.

And I hope I never have to write about banks again, because although the failures are unique, and the contributions from bad luck and incompetence vary, the lessons and call to action don’t really change, do they?

The content provided in this document is for informational purposes and does not constitute a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to purchase or sell securities. Nothing should be considered personal financial, investment, legal, tax, or any other advice. Content is information general in nature and is not an attempt to address particular financial circumstance of any client or prospect. Clients receive advice directly and are encouraged to contact their Adviser for counsel and to answer any questions. Any information or commentary represents the views of the Adviser at the time of each report and is subject to change without notice. There is no assurance that any securities discussed herein will remain in an account at the time you receive this report or that securities sold have not been repurchased. Any securities discussed may or may not be included in all client accounts due to individual needs or circumstances, account size, or other factors. It should not be assumed that any of the securities transactions or holdings discussed was or will prove to be profitable, or that the investment recommendations or decisions we make in the future will be profitable or will equal the investment performance of the securities discussed herein.