“I’ve been asked if I have any regrets. Well, I do. The deficit is one.”

– Ronald Reagan on his televised farewell address, January 11, 1989

“Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”

– Dick Cheney to Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill’s on concerns of rising debt, 2002

“Yeah, but I won’t be here.”

– Donald Trump to concerned senior staff presenting spiking debt projections, 2017

Almost 23 and a newly licensed investment advisor, I had no business dispensing investment advice, much less speaking to groups. Yet there I was, at senior residences, professional associations, and wherever else the company deployed me, not knowing the extent of my ignorance or that I was just high on that sense of confidence and promise befalling recent Harvard graduates. (Thankfully, it doesn’t last.)

My presentations were the stuff of an economics major, dry and not entirely relevant or useful: how higher GDP growth and its levered effect on tax revenues were the only path to closing deficits; why tax policy matters; and, my favorite, the inevitable disaster that is demographics and entitlement spending.

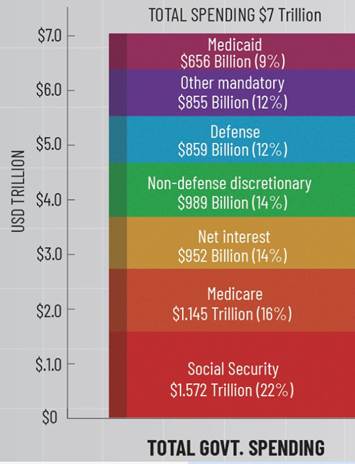

I didn’t know much, but I knew all about the Ponzi schemes the U.S. and other developed nations were peddling. The math was simple: The Big Three entitlements (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) comprise most of the government’s spending and are gaining share by the day. Add interest on debt and obligatory defense spending, and almost the entire federal budget is accelerating to some point of no return unless some hard choices are made.

To younger audiences, I’d conclude with the case for saving early and consistently; act as if Social Security won’t be there in the future. To older audiences, I’d make a case for conservatism in investing; a worsening fiscal picture means higher risks for stocks, yada yada.

What a schmuck I was, telling people how to run the world.

I have been thinking about those early days in the business a lot lately as I read about the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the latest budget reconciliation bill from Donald Trump and House Republicans. I think about how much has changed, how the fiscal trajectory I was so worried about back then has only worsened since then—and how resilient (or complacent?) all of us have been in the process.

Doom hasn’t come—yet.

20-something years later, I still worry about deficits and the debt. The math is worse now, so much so that maybe soon even reasonably achievable economic growth targets may not be enough to stem the tide. I have no idea. Let’s just say I wouldn’t give the talks the 23-year-old me would.

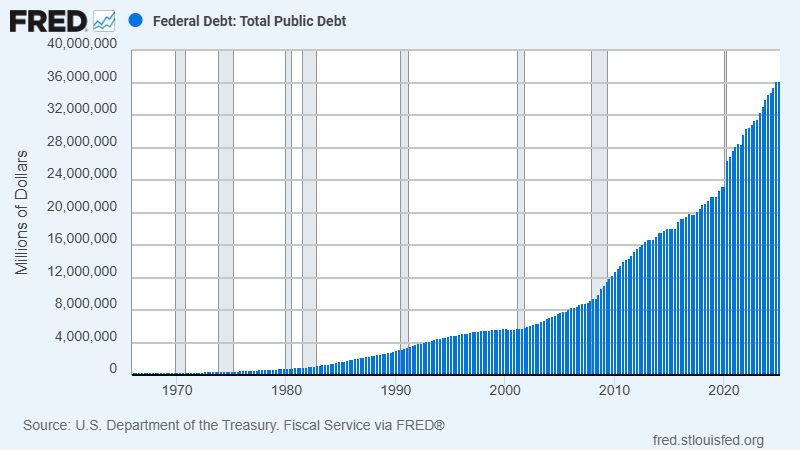

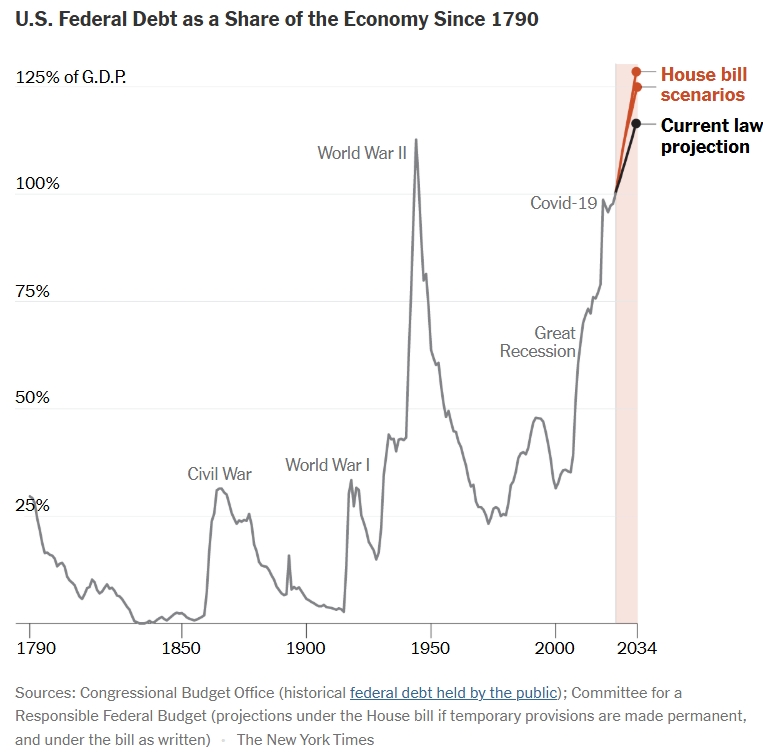

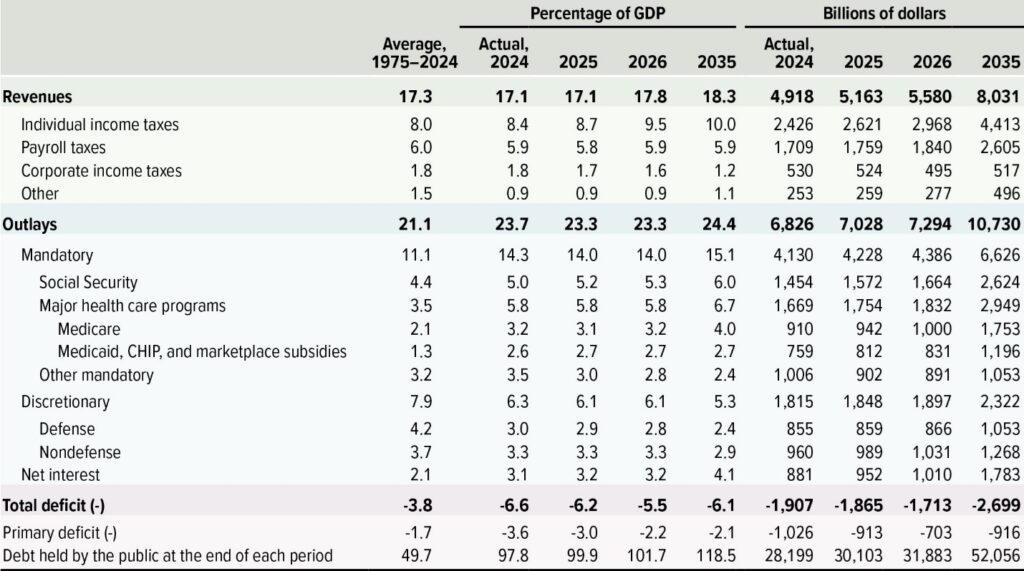

The national debt today is over $36 trillion, representing over 100% of GDP. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the debt will exceed $52 trillion by 2035. And, if history repeats, actual numbers in 2035 will exceed estimates.[i]

Shifts politically have contributed to this, of course. Democrats have moved far left of the Bill Clinton’s New Democrats. Most Democrats now identify as Progressives and are increasingly critical of capitalism. The national debt is far too low, they argue, especially since the U.S. prints the very currency it owes.

But it’s the change in Republicans over time that has been more drastic. Over years and decades, cornerstones of free trade and fiscal soundness have almost disappeared. For all the talk of polarized politics, Trump’s MAGA politics—now the GOP’s—share much in common with Progressives. Both view economics as a zero-sum game, both are anti-trade, and both believe debt and money printing to be consequence-free remedies.

I think it’s reasonable to act as if America’s fiscal Doomsday Clock has ticked closer to midnight (Europe and Japan’s, too, maybe more so).

What I won’t pretend to know—unlike that 23-year-old rookie—is what the consequences are—or especially when. Is the clock at 8pm or 11pm? At midnight, what then? Crashing fiat currencies, including the dollar? Austerity measures? Runaway inflation? Soaring interest rates and persistently low economic growth? Lower standards of living?

It’s all possible, and it seems wise not to forget that. So we invest with an extra margin of safety, a healthy amount of cash equivalents, and stay liquid. We get even more diversified, even if it means investing in things we’d rather not, like gold and silver.

We avoid investments that require perfect weather, are priced to perfection, or face lots of competition. Only reasonably priced stocks of companies of true and enduring value, companies deserving of growth and appreciation over time.

We get more skeptical of long-term bonds, knowing a main threat is inflation rising higher than the market’s assumption of 2.3% annually over the long-term, and instead take the “over” on inflation and get protection on the cheap with inflation-protected Treasurys.

Mostly, we keep an open mind and not wed our fortunes based on hard forecasts and hubris.

And we stay humble and grateful and remember what is truly important.

Neil Rose

Post Script: I can’t help but make a few observational points considering how the media reports fiscal matters and large numbers. Granted, numbers get so large that they are hard to comprehend; they almost become conceptual. Also, I suspect media is too influenced by the language used by politicians.

Point 1: Deficit and debt are not the same thing.

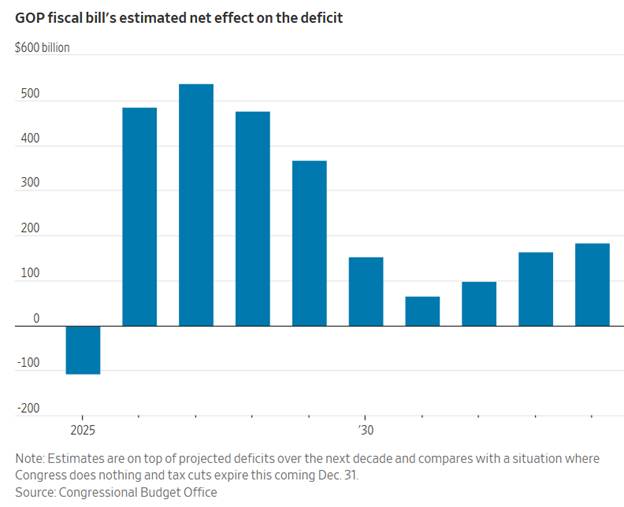

Numerous headlines state the new bill will add $2.4 trillion to the debt, but that’s not correct. It should say $2.4 trillion in additional deficits on top of the deficits already forecasted to 2035. Debt is the total of all deficits and surpluses.

Even the Wall Street Journal doesn’t get this exactly right. The chart below would be better if the blue bars were presented stacked on top of future deficits scheduled, which already average well over $2 trillion per year until 2035.

Point 2: Know the important numbers. Much of the rest is noise.

Every citizen should know the basic government math, especially before they take hard policy opinions about how much money to get, where to get it, and where to spend it.

Currently, the government collects about $5 trillion a year in taxes and spends about $7 trillion. U.S. GDP is about $30 trillion. The $2 trillion in annual deficit is almost sure to continue growing faster than GDP. Budget | Congressional Budget Office

The government already projects the official debt to be $52 trillion in 2035 and over 125% of GDP.

The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035 | Congressional Budget Office

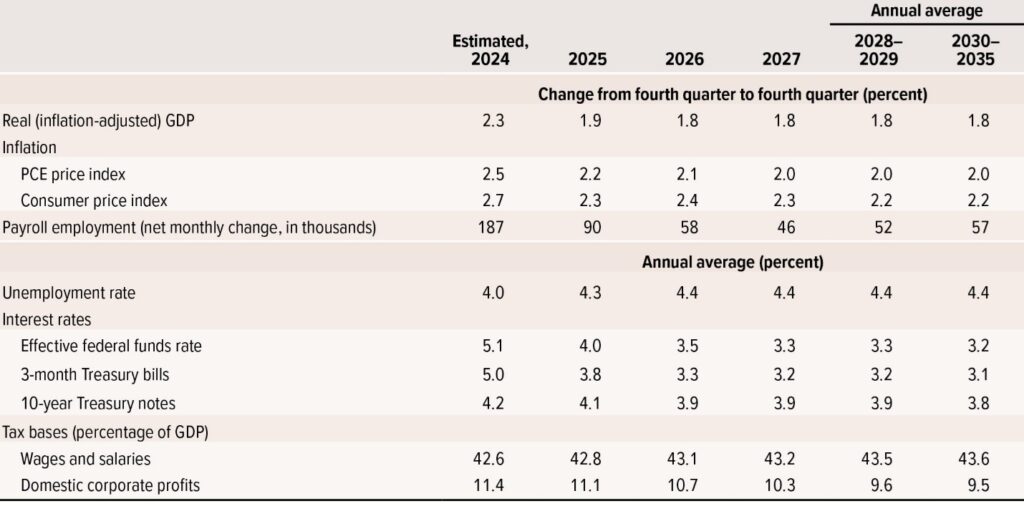

Point 3: Remember, forecasts are flimsy and are built on benign economic assumptions

To make a 10-year budget forecast is to have assumptions about economic growth, inflation, and other factors. That’s why estimates are often wrong and should not be taken as gospel. However, the direction of deficits and debt is highly likely regardless unless you assume imminent and significant changes to future entitlement spending.

The economic assumptions below account for no recession (or at least not material ones), benign inflation, and interest rates a bit lower from where they are today.

Point 4: Know the important numbers (again). Most spending is on autopilot.

Non-defense discretionary spending is set to be about $1 trillion—only 14% of the federal budget. Defense (considered discretionary) is $900 billion, or 12%.

The rest—74% of the total federal budget—is non-discretionary and subject to automatic increases. Inflationary pressures are a major point of uncertainty about actual spending growth.

Source: 2025 HR1, Economics Insider

Point 5: Cuts are not really cuts

A debate I heard on NPR was the latest reminder of the importance of not just numbers but also terminology. “Cuts” to budgets, Medicaid—you name it—rarely mean a reduction in spending versus today. Rather, they mean a cut in the scheduled increase in spending (or a lower increase).

So, a $1.0 trillion spending item may see a future “cut” to $1.2 trillion—if $1.3 trillion was already scheduled.

Absolute versus relative matters.

[i] Important to note that the debt doesn’t count the “off-balance sheet” but very real liabilities of future entitlement shortfalls. Off-balance sheet debt could be $100 trillion, give or take, if presented in present terms the way unfunded pension liabilities are shown on a corporate or state government balance sheet.