In his 2011 book Debt: The First 500 Years, anthropologist David Graeber lays out the historical concept of debt, starting with the Sumer, the earliest known civilization, located in historical Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE.

Graeber thinks debt and credit predate money itself. Farmers would borrow ahead of the harvest. The first loans might have been payday loans.

Debt and credit’s long history brings added significance to the events of 2020, when Covid put into overdrive a decades-long trend of declining interest rates that ultimately reached zero and less.

Never before had the market-driven price of money (that is, market-driven interest rates determined by the supply and demand of loanable funds) been so low, so cheap. There is no evidence borrowers before 2020 had ever been paid to borrow with a negative interest rate.

It was a special kind of speculative bubble to the suppliers of credit, including investors in long-term debt securities: ultra-low rates meant extremely dear prices for bonds.

The low-rate/high-price for bonds could not be done without a historic appetite for bonds, of course. Bond buying only went up even as investors received less and less value for their money. Somehow, bonds were not perceived to be riskier, quite the opposite.

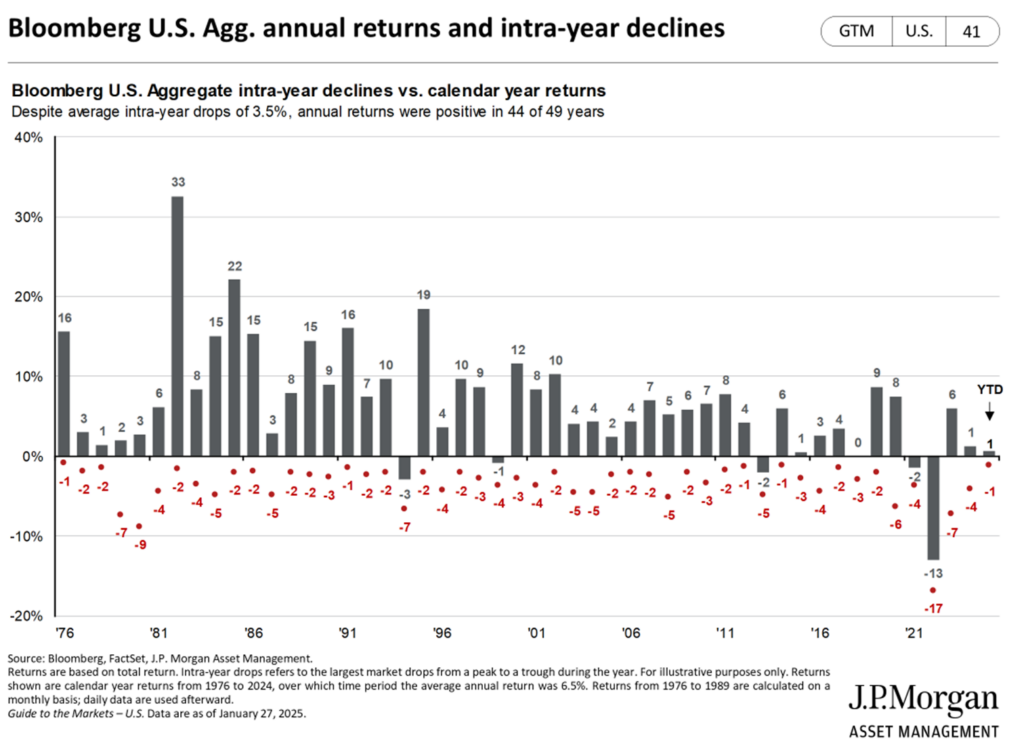

2022 brought some sobriety. Stock prices dropped, but long-term bond prices dropped much more. More than a few banks failed due to losses in their bond portfolios, including the revered Silicon Valley Bank.

Over the past five years, bonds—as represented by broad bond indexes—are not yet break-even. Investors in longer-term bonds (like banks) are still underwater. Most bond investors have received return-free risk instead of something closer to risk-free return.

While not vacating bonds completely (because going “all-in” on any thesis poses other kinds of risk), we kept bond allocations low since our firm’s Day 1 at the start of 2021). We also shortened the average maturity of what bond exposure we had.

A good amount of losses were avoided, and we anticipated we would be in a better position to invest once the interest rates inevitably rise.

Lots of cheap money inevitably caused an inflation scare, and the Federal Reserve raised short term rates starting in early 2022. In 18 months, the Fed raised rates 11 times, from near zero to nearly 5.5%.

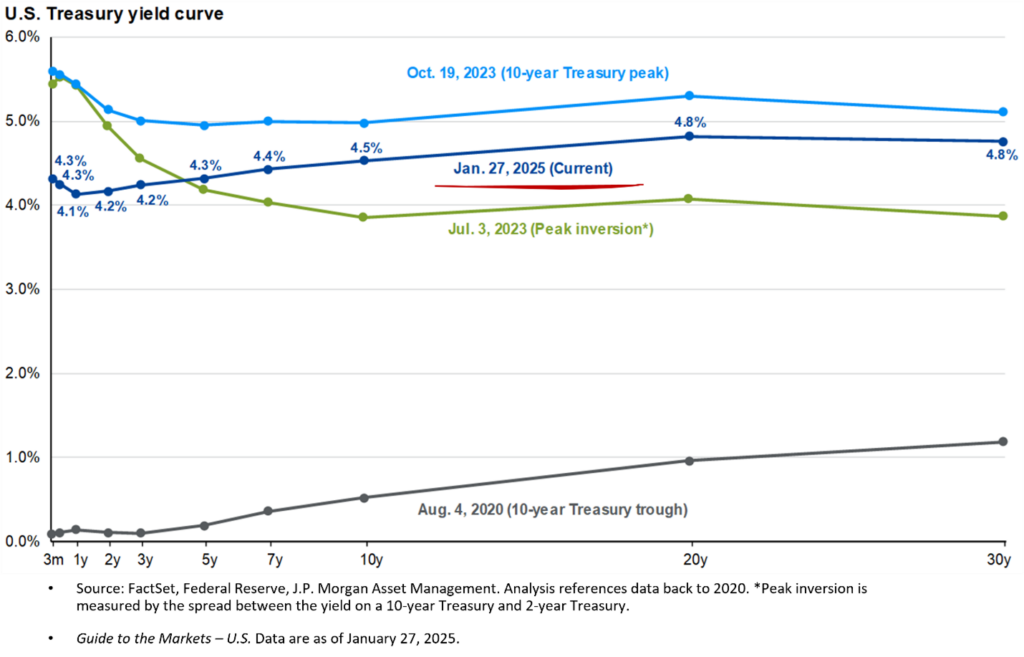

The Fed lowered rates somewhat starting in August, 2024, in anticipation of a recession that hasn’t yet come. At a 4.25-4.50% policy rate, the Fed is now confused between inflation and deflation given economic data and the prospects of Donald Trump’s tariffs. Regardless, there has been a sea change in interest rate policy. Investors are now getting paid decently for parking money with Uncle Sam.

In all but our all-equity portfolios, we have been accumulating bonds and increasing our holdings’ average maturity. This is mostly due to a fortuitous raise in longer-term interest rates.

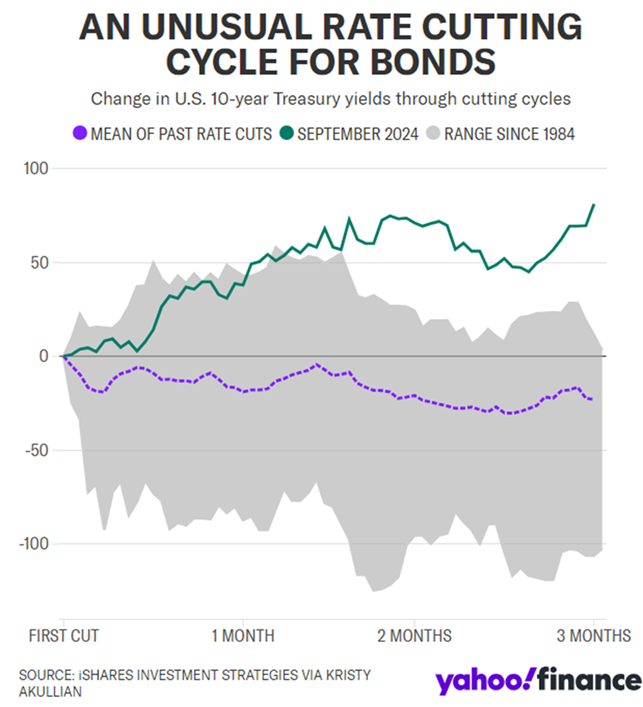

Typically, when the Fed raises interest rates, longer-term interest rates do not rise materially. They often go down as the market anticipates tighter money means lower inflation and higher likelihood of recession.

That hasn’t happened this time: longer-term rates have risen instead. For new investment, that’s a welcome development, of course, but what makes it more so is that the rise is not due to higher inflation expectations, but rather a rise in real yield.

Today, bond prices represent a positive real yield—among the highest of the past two decades—on top of inflation. Not long ago, real yields were negative.

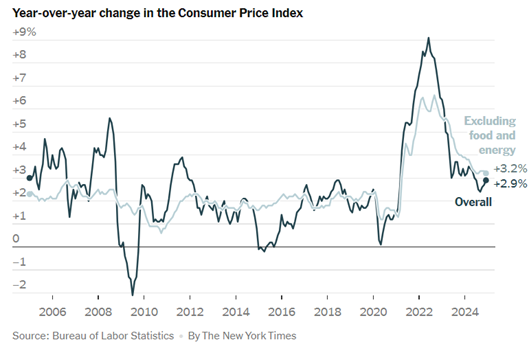

One of the principal risks to bonds or anything with a fixed-income is inflation, or more specifically, future inflation that is higher than estimated.

That the market’s expectations for longer-term inflation is low and haven’t budged much over the years says a lot about its high confidence in government and central banks. But it doesn’t take a wild imagination to think of a world where annual deficits in the trillions funded with printed money ultimately leads to more inflation.

This isn’t a forecast, but a recognition of a risk, one that is at the top of the list in the context of the long-term.

To somewhat hedge inflation risk and the notion that the crowd might be wrong, it makes sense to look at Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (or TIPS) and include them in bond holdings, especially when hedging inflation is reasonably inexpensive. I think that’s the case now, especially given this convenient feature about TIPS: while a holder receives inflation protection (as measured by CPI) in the form of an increase in the bond’s principal, a holder doesn’t necessarily lose money if inflation is negative—meaning deflation reigns over the maturity of the TIPS.

In other words, TIPS have a floor to them, which means hedging an important and open-ended risk like inflation doesn’t come with a huge cost of being wrong. We like that.

Even with all the bond buying done over the past six months and more, we are far from being heavy in bonds. Should rates go up from here—especially real rates—we will happily buy more.

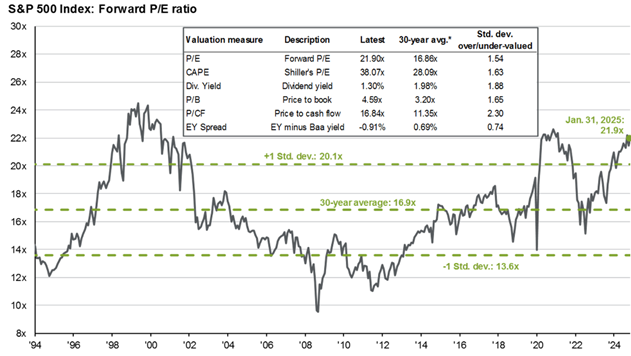

There is another argument to be made for bonds: stocks have had a huge run and are not cheap, and higher interest rates are a significant risk for high prices and P/E multiples.

Bond prices and investor sentiment have changed over the past five years. Today, investors clearly favor stocks and worry about bonds. Stock allocations are up to historical highs among institutional and individual investors. Overall optimism is arguably higher than ever, as is the stock market’s average P/E.

When the market can earn more in bonds, it naturally starts to question the merits of paying high prices for stocks. High prices also mean there is less room for error regarding company earnings, economic growth, even geopolitics. High prices and multiples mean perhaps a lot is baked into the cake.

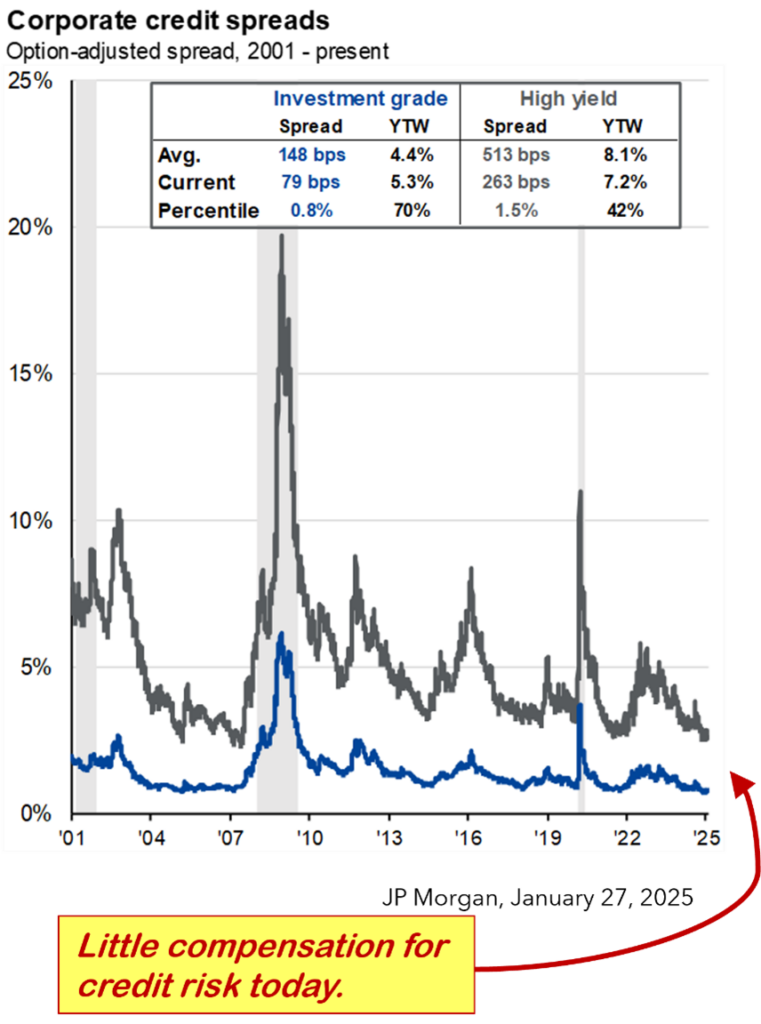

Credit spreads also reflect market optimism. This means investors aren’t getting paid much more for additional credit risk. It makes sense to me to limit corporate bonds in favor of Treasurys.

Additional Charts:

BOND RETURNS

INFLATION

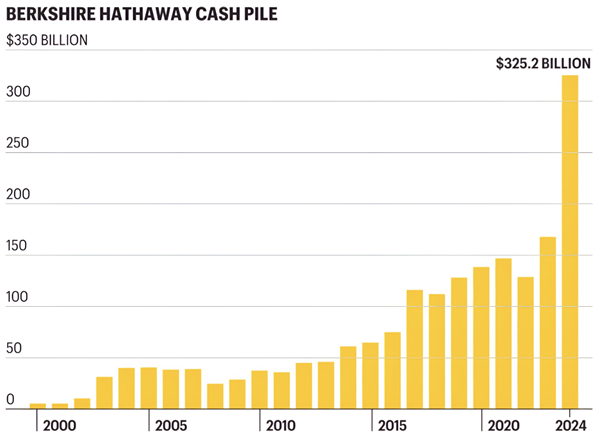

WARREN BUFFETT holding record cash says what he thinks about stocks.